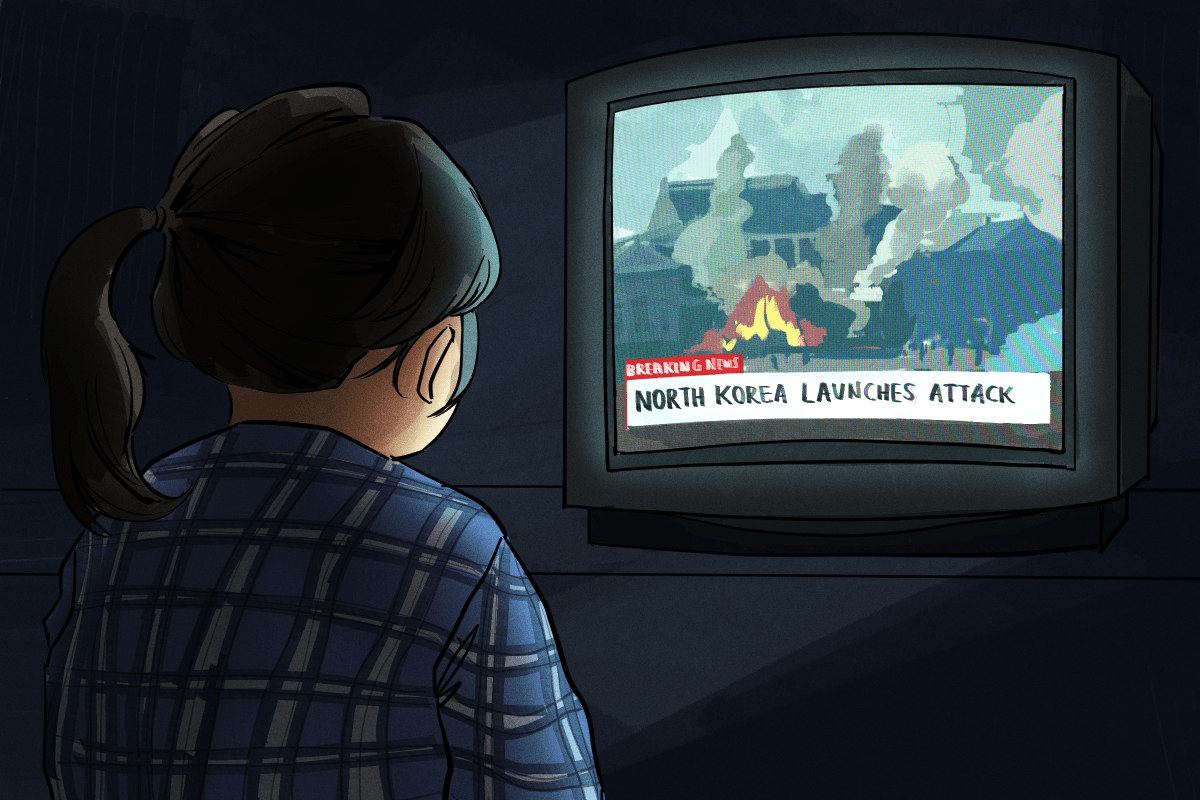

Growing up in Seoul, all of the information that I was fed about North Korea compelled me to fear the country. As an 8 year old in 2010, I remember coming home from school wide-eyed with fear after hearing the news that North Korea initiated an attack on Yeonpyeong Island, the northwestern border island situated between North and South Korea. The blank expression on my mother’s face as I got off of the school bus, the strongly-worded news clips rattling the nation and my trouble falling asleep at night all remain vivid memories inside of my head. Even at such a young age, just the thought of another bloody conflict frightened me. To this day, I pay careful attention to any story related to North Korean affairs.

My country is one that has clawed itself out of poverty. South Korea is a country characterized by resilience, resourcefulness and han (한), or the feeling of collective grief and sorrow that the people of Korea share. While more and more of America and its culture is influencing me as I study here, I am always proud of being a Korean citizen. The more I attempt to trace my roots, the more I have to remind myself that while there are currently two Koreas, they started off as one.

As I developed an interest in journalism and North Korean affairs, I could not shake the impression that Western media covers North Korea in an incredibly biased, hyperbolic manner. While it is no longer surprising to hear the typical “little rocket man” comment, I am always met with a pang of concern when I realize how most of the world associates North Korea with nothing more than nuclear weapons, poverty and a third-generational dictatorship.

Western media has been criticized for its imperfect coverage of North Korea for years. Stories about North Korea are often popular, as the public views the isolated, frozen-in-time country as a form of entertainment. And indeed, provocative stories speculating that Kim Jong-un banned leather coats, lost a lot of weight or entered a coma can truly spice up a boring day at work. As a result, journalists are strongly tempted to derive quick, provocative conclusions that lack credible sources or fact-checking to rack up hefty views and subscriptions.

This profit-driven mentality is not a new problem, nor one exclusive to the coverage of North Korean affairs. The problem is that Western media applies too much of its own interpretation when approaching the country of North Korea as compared to its coverage of other nations. As a result, in the process of producing content tailored toward maximizing the number of clicks and gasps, accuracy no longer takes priority and false or unfounded information is published. As a result, there is an overemphasis on negative news when it comes to stories related to North Korea.

Western media often focuses on negative news and events in North Korea, including human rights abuses, nuclear threats and missile tests, while ignoring positive developments or avoiding the coverage of other topics altogether. When topics such as the culture of the country or the plight of North Korean defectors are overlooked and unaddressed, North Korea will not be understood in a comprehensive, rational manner. A lack of sufficient context and historical background of a nation-state can be extremely harmful, as it can lead to a distorted understanding of the country and its political situation.

While informing the readership of salient national security issues is necessary, it is concerning when such information becomes muddled with sensationalist, inflammatory language. Reporting accurate, fact-based information is the most viable way of preventing the masses from perceiving and replicating a skewed picture of the already-misunderstood country. When such principles are agreed upon and met in news covering domestic and other international affairs, it is difficult to grasp why the same understanding cannot be extended to North Korea. The harms of continuing such practices are as clear as day, and threaten the foundations of journalistic integrity and ethics.

Of course, one could form the argument that there is not enough reliable information carrying news from official North Korean sources. After all, North Korea does have extremely high levels of censorship and security, and the Kim regime can be highly selective with the information that they share. However, shifting the blame on North Korea is nothing short of justifying pure ignorance; North Korea cannot be blamed for outright bad reporting, and it is the responsibility of all journalists to conduct proper research before publishing stories that will be read by a frighteningly large, diverse readership. Good research starts with talking to qualified experts, rather than picking up stories from other outlets or heavily relying on biased sources.

Instead of resorting to sensationalism and exaggeration that distorts the readership’s understanding of the country, Western journalists should make more active, genuine attempts to converse with reputable North Korea experts that may not necessarily speak their language. The Sejong Institute, The Asan Institute for Policy Studies and the Korea Institute for National Unification are just a few of the major South Korean research institutes conducting research on the Korean Peninsula. In addition to consulting more credible sources, media outlets ought to hire reporters with an eye for journalistic integrity and ethics, topics briefly mentioned during the first few onboarding meetings early in one’s career then often forgotten altogether.

The media’s flawed coverage of a country impacts real people and bears horrible consequences. During my time serving as president of my home university’s only central club dedicated to North Korean matters, it pained me to learn firsthand that thousands of North Koreans who have relocated to the South struggle with discrimination and prejudice from South Korean society. Unsurprisingly, such comments were almost always paired with the observation that media outlets paint the North Korean state and defector community in a negative manner. It’s about time journalists distance themselves from poor research and start putting in the hard work that goes into a good, truthful article about real people.

Every day, I try to sweep aside what I write on my resume, what I tell my parents and what I say when asked about my goals. When I’m not an “undergrad interested in pursuing opportunities in politics, law and international affairs,” I am a college junior born and raised in Seoul, South Korea. I want people to better understand my country, and to understand the stuff outside of kimchi, K-Pop and speculations of a nuclear war. Surely, there is a consensus that media outlets should strive for accuracy, objectivity and fairness in their coverage of information, including content about history and North Korea. This consensus should include providing context, seeking out diverse perspectives and sources, and avoiding inflammatory language or bias.

From Seoul, South Korea, So Jin Jung is an Opinion Columnist with a passion for politics and journalism. She can be reached at sojinj@umich.edu.