Something is currently wrong with me, with the way I’m living my life right now. To figure out what, I’ve decided to go over the following: this sample I wrote over a year ago while applying for The Michigan Daily’s Arts section on comedian Bo Burnham’s “Inside” — a sample I remember spending a full day locked in my apartment working on through multiple drafts and angles. Rather than editing the content itself (except to align with The Daily’s style), I’ve decided to annotate it instead. These sections will serve to update and contextualize my previous writing. Just as “Inside” was a time capsule of life during the pandemic, this piece is my personal time capsule of almost a year of post-pandemic life — perhaps a simpler time, maybe a better time, a time I was living my life correctly. Let’s unbury it together.

Almost a Year Later, Bo Burnham Reminds Me to Go Outside

I first watched “Inside” at the age of 19, the same age Bo Burnham (“Eighth Grade”) debuted his standup comedy after years of being a YouTuber. It was released after over a year of the pandemic. My immunocompromised status left me in a heightened state of physical isolation from my friends and emotional isolation from my family. Watching “Inside” after being fully vaccinated and reuniting with my friends felt like a flashback. It made me feel as if I was regressing to the hollow shell of myself quarantine turned me into.

Fun fact: The first sentence is factually wrong. Burnham started performing at age 17 but was 19 when he released his first special, “Words, Words, Words.” Anyway, that’s quite the note to start on, no? This paragraph actually started the last section of this sample’s first draft. I figured all of the analysis would happen, then I’d dedicate the last section to my personal angle. That conclusion ended up being nearly as long as the analysis itself, so it had to be cut up somehow. I opted for spreading it out through the argument, to switch between the two modes as a creative form and as a tribute to the dualism of “Inside.” It kind of slaps you in the face with my disability and my mental low points right out the gate, and then immediately pivots to a completely different subject — not unlike the special. I don’t know if I’d start an article that way now. Before we get intimate with my issues, we need some foreplay, right?

Satirizing issues surrounding mental illness is difficult because satire requires elevating a concept to irrational heights while mental illness seems to normalize that irrationality. Burnham’s “Inside” thusly (sic) presents its theme in layers of satire surrounding a myriad of other topics including but not limited to the coronavirus pandemic/quarantine, the current capitalist-exploited sociopolitical climate and social media’s corrosion of society and self. However, a common criticism of the work is that when you pile so many layers of meta, irony and self-reference, it reduces the base message to nothing of value. This is something that “Inside” does acknowledge. It’s very easy to feel like you’re drowning in the layers of irony that you’re drenched in, to the point that everyday existence feels like your last seconds of trying to just get a breath of fresh air. Burnham dives into these waters, and like a deep-sea documentographer (sic), goes as deep as he can to see if there’s something worth it on the other side.

The thesis of this article came from two TikToks I watched that were originally mentioned in the first draft. The first was a man who watched cooking videos and got criminally offended if any ingredient was even the slightest bit unhealthy, and the second was someone else stating that aforementioned “common criticism” — that this self-layering negates any genuine meaning. While I just wanted to challenge the latter, the former was more interesting to me since comments would claim the man was satirizing eating disorder culture — but the reality is that behavior could still trigger symptoms of eating disorders. Irrational elevation still mimics and can even trigger irrational behavior. So take that irrationality and layer it with other irrationalities until you find … something? Something true, something real, something that is left after all the bullshit of the world is blown away? I think when I began with that thesis, I just wanted to talk about something different than all the other discussions surrounding “Inside.” I wanted what I said to matter. I want anything I say to matter. Maybe I’m unsure if it does anymore, if my actions do.

Listening to the special’s soundtrack when I was forced back home after cracking a bone in my leg last semester flashed me back again. I couldn’t bring myself to rewatch it until snow barred me and my classes inside. For the sake of writing this piece, I let it play in the background while cooking lunch for myself in my apartment. I have three roommates here, but we’re all so busy with ourselves, it feels like I live alone — my girlfriend or a friend coming over occasionally giving me brief respites from isolation.

Those people are gone. I have more people in my life now, though it’s usually me going out for respites from isolation instead of others coming to me — the consequences of a North Campus apartment (I’m moving to Central Campus soon). Part of me wants to explain more of the details of that living situation, but most of me knows it doesn’t contribute what I once thought it would. Yes, I’m getting personal, and yes, that helps to make it distinct — it connects this piece to me. But does that actually improve this article? I’m no longer sure. If I didn’t discuss this, would you be more or less engaged? And that issue raises its head again — I think externally these conditions have improved, but then what’s still wrong with me?

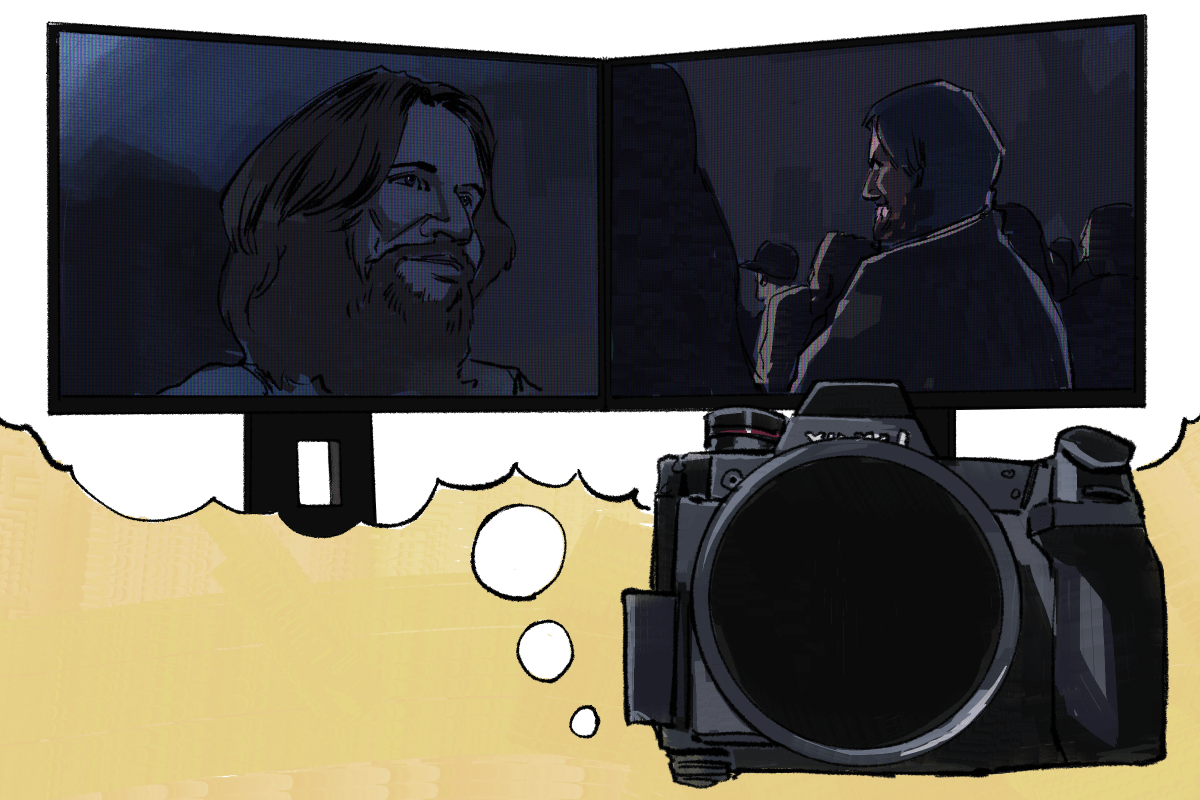

An important distinction has to be made in unpacking “Inside.” The fact is, Burnham is incredibly vulnerable in this work but is also incredibly dishonest. Burnham is starring as and compartmentalizing into his character Bo. Evidence for this is littered throughout the special, but a scene where Bo is waiting for midnight is the titular example. He waits for the day to pass into his 30th birthday, presumably when the clock changes from 11:59 p.m. to 12:00 a.m. However, in the beginning of the shot, you can see daylight filtering through the window. Bo’s breakdown: His delusions, his suicidal thoughts, even his scraggly hair are a character that Burnham manufactures and presents. Burnham’s experience informs Bo but does not indict Burnham in Bo’s insanity. Bo stares into the abyss of his filming camera, and it stares back. Burnham stared into the abyss within himself and became willed to fill it.

I only noticed this scene’s details from a TikTok analyzing it. I’m particularly proud of the last three sentences, especially considering, again, it wasn’t just describing something I saw on TikTok. What’s special to me about Burnham’s choice is that his choice to hint at his dishonesty makes the piece more honest. Every entertainer lies to you — their very nature is performance, made even more ridiculous by the privilege they experience while pretending to relate to their audience. What separates Burnham’s performance from an hour-long version of those celebrities singing “Imagine” is that Burnham constantly reminds us it’s a performance. But more than that, Burnham’s methods became an object of my personal fascination: How could you reveal everything about yourself — these irrational behaviors, these bits of trauma, these honestly-worrying admissions — while being ultimately invulnerable under the facade of vulnerability? How could I do that? More importantly — how could I make it matter? Does pain matter simply because it’s pain? Or is the world so filled with it you have to dress it up in whatever way you can?

At one point, I just made a rule for myself: The only personal topics written for publication would be what I had processed in therapy. The fact is I’m physically disabled and mentally ill and I want to be a better person than I’ve been because one day I won’t be able to. All of those lengthy articles linked could be boiled down to these simple facts about me. Every time I publish something, it becomes a little time capsule all of its own, of the different person who wrote it. Maybe what’s wrong is the hole I’ve dug for myself here. I’ve always wanted to be a writer who could be vulnerable, but maybe all I can think of doing now is peeling off layers of myself to publish until I’m naked to the world. Peeling off layers until I’m skin and bone, until I’m just nerves and electricity, until I am nothing left.

I watch Bo as I chop vegetables to bake and boil pasta. I pause the player to audibly laugh at visual gags I didn’t see before. I shrug when he asks if he’s on in the background. I lightly dance to the beat of Bo singing about how he feels like shit, revelling (sic) in the use of my still-healing ankle as I stir the baked veggies and penne together. I finish cooking and bring my laptop back to my monitor with food, still watching as I have my meal. I finish eating as the special reaches its emotional climax. While the irony of needing to overstimulate with “Inside” is not lost on me, I focus as the final song reprises the entire special. I look down at the circular mirror that sits below my monitor and my layers are blown away. As Bo ends the special with a twisted smile, I remember the picture I saw of him watching Phoebe Bridgers perform a cover of his song. With every layer peeled away, I am nothing, nothing but the people I love. Every single one of us are nothing but those we love. Isn’t that such a wonderful paradox?

That’s why isolation makes us feel like nothing. Burnham genuinely smiling at a crowd enjoying his song reminds him and us that isolation eventually ends. The irrationality that isolation can plunge us into is exposed for what it is, and Burnham becomes a rich white man pretending to cry in a $3.25 million dollar guest house. The tension rewatching Bo releases as I take a breath of fresh air. My beard and bedhead hair are reflected in the mirror and in Bo, and realize I need a trim. I’ll get one tomorrow, when I go back outside.

I didn’t actually get that trim for months — I need one now, to be honest. But that moment of true vulnerability, where it finally feels like Burnham drops the facade, is more important to me. There’s the look of plain disgust when he concludes in his first special that “art is dead.” In his following special, he chooses a finale literally orchestrated by his naysayers and just dances to the art made of it in “We Think We Know You.” In his last special before “Inside,” he can do nothing but scream at the audience, reminding them that he “Can’t Handle This” because he had started to experience panic attacks during onstage performances. Then there’s that very last frame of Burnham smiling in “Inside” to grinning (perhaps) more genuinely at Bridgers’s performance. Maybe this is what we need — we need to believe the only real thing underneath all the layers of life and art is the joy to participate in it.

“Inside” no longer brings that feeling of regression within me. It encapsulates all of this metamodern melancholy the way my article reflects my own post-pandemic anxiety, but now I just smile at the joy of being able to create and live. It’s a joy I’m feeling right now, one that I’ve been so blessed with for so long. So I should stop lying, too: There’s nothing wrong with me. I’m actually doing fine — great, actually, in large part thanks to the people that form me. If I’m being honest, drawing back on my painful experiences to write has just become kind of stale for me, so I find myself needing to make it a little more interesting.

When something dramatically alters your life, something that changes how you live it day-to-day and invites questions about it from others, it just becomes pragmatic to have writing on it to already answer those questions. That’s how this all started. But if I’m nothing except the other people in my life, wouldn’t it be natural to give that all back until I’m nothing again, until the people in my life restore me again so we can all keep giving back to each other? What has become more important to me in art is not what one reveals about themselves, but how they reveal themselves: One indicates experience, the other artistry. But if just one person feels seen or helped by what I’ve written, then it was more than worth it to reveal myself — what I did was enough to matter. But that’s enough out of me. I’ve been stuck inside too long writing this. I’ll meet you all back outside. Oh, and Bo — thank you, you weird man.

Summer Managing Arts Editor Saarthak Johri can be reached at sjohri@umich.edu.