College decisions week — the shared traumatic experience that binds most graduating high schoolers. Staring at your laptop, refreshing the page every 10 seconds, with your heart pounding and throat dry; your body heavy with the expectations of your parents, teachers and counselors while you convince yourself that if you see the word “accepted” on your screen, it will change the trajectory of your life. It was no different for my friends and me in Mumbai, India — except that for us, American college decisions would be released at 5 a.m., prompting hellish nights of agonizing insomnia. Every time my phone lit up with another “I GOT IN!!” text from a friend, I felt a mix of panic and pure happiness before I’d dutifully pen the “CONGRATULATIONS! AAAAH” text back, with a few emojis thrown in for good measure. In all honesty, I was afraid of the massive changes that would bulldoze through my life in just a few months. All my friends and I were being scattered around the globe like dice on a board — some staying in India, some off to Canada, the UK, the Netherlands, Australia, Italy, Scotland and, of course, America.

More than two-thirds of my graduating class from the Bombay International School are now pursuing their undergraduate degrees abroad. Most of my friends headed to universities in cities like Boston, New York and London — large, busy, chaotic cities that we felt at home in. Moreover, all these cities were extremely diverse compared to Ann Arbor — a much smaller, quieter college town that I had never even visited. While applying for my student visa and making packing lists for my move to a new continent (some advice: extra socks always), I convinced myself that I would be just fine. So what if I’d be a few thousand miles away from my family? Didn’t my father do the same when he pursued his degree? Considering the reputability of Midwestern hospitality, how hard could it be to make some friends in Michigan? So what if they called a dustbin a “trash can”? Surely I could show them the light. I squashed down all my doubts and fears, determined to walk into this next year with an open mind.

The culture shock I experienced was not just the result of moving from India to America — it was also adapting from life in the ninth largest city in the world to a small college town known for housing the “cultiest college in America.” It was difficult to fall asleep without the cacophony of honking cars and barking dogs soothing my ears and the bright yellow street lights shining through the curtains guiding my dreams. Whenever I couldn’t sleep back at home, I’d head to my living room and look out the large double windows which overlooked a busy flyover (or an overpass, as Americans would say). From my vantage point, no matter what time it was, there was always a steady stream of cars zooming by. There were also always a few small squares of light shining in the apartment building windows in my peripheral view, even at 3 a.m. As I stood in the room alone and frustrated, this sight would be a comfort to me. All these people, just a few hundred meters away from me, were awake and present at the same moment. And suddenly the night would be less scary and isolating. When I couldn’t sleep in my dorm room in Mosher-Jordan Residence Hall, I tried looking out my window to do the same … only to see a deserted cemetery and not a whisper of movement for hours.

The skyline of Mumbai in all its glory, with shadowed silhouettes of shapely skyscrapers, was now replaced by low brick buildings revealing miles of open sky. The mustached street vendors selling hot masala chai to tired office workers had morphed into teenage baristas in green aprons whipping up iced lattes for frazzled students. The fervor of the Mumbai versus Chennai IPL cricket match at Wankhede Stadium, with a sea of fans in blue waiting with bated breath for a six, was now mimicked by the fated MSU versus Michigan football game (a sport I tried hard to understand but gave up on while I still had some dignity). The tall palm trees lining the streets waving in the salty sea breeze were now towering sugar maples with deep orange leaves. My weekly vices changed from butter chicken and mangoes to an incredible amount of No Thai and dining hall cookies. But a greater challenge than the lack of spice in the food or being met with odd glances when I said my favorite football team was Real Madrid (it just feels wrong to call it soccer) was adapting to being a racial minority for the first time in my life.

My Indian American roommate (I used to ignorantly call her American Indian before she found out and gave me a comical reprimand) was used to this. However, growing up in Mumbai, I was never a racial minority simply because there were practically no other races present in my city. Mostly everyone in my city and state spoke the same languages I did. We all celebrated the same festivals and ate the same food. There was a uniformity in Mumbai that never made me feel out of place and a relatability and harmony that I didn’t find present in America. Every day in school, we would recite the pledge: “India is my country, and all Indians are my brothers and sisters … ” Never will you feel this as keenly as in Mumbai. I could strike up a conversation with my taxi driver about the construction of the upcoming Mumbai Metro system, or I could run into the arts and crafts store near my house right before it closed, begging the shopkeeper for some color pencils for a school project. Both of them I would address as bhaiya. Bhaiya is the word that my lips miss shaping the most — bhaiya, do you sell the spicy Lays chips here? Bhaiya, can you help me carry these bags to my car? Bhaiya is the Hindi word for brother, used in Mumbai to address just about anyone, from a watchman to a bus driver.

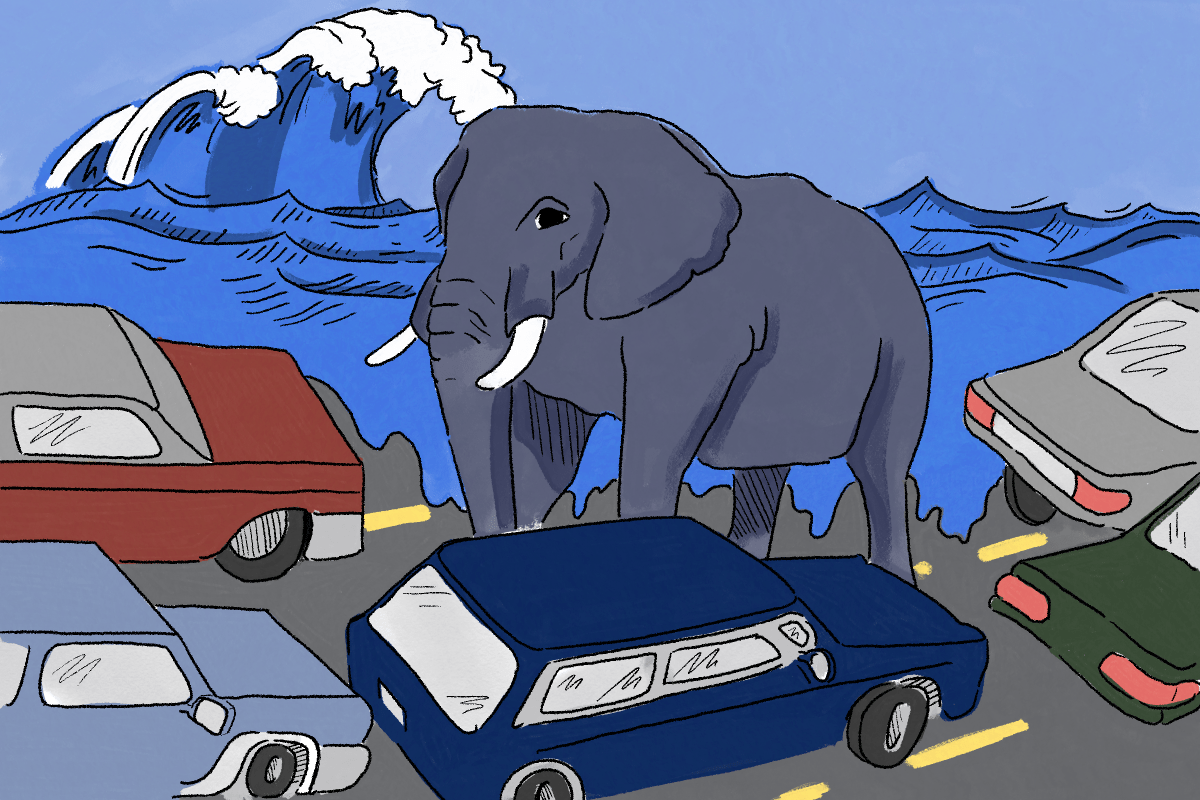

On an evening in early October 2022, I sit at a crowded table in the Math Lab at East Hall, occasionally asking the busy instructor a calculus question pertaining to the upcoming midterm. Two blonde girls strike up a conversation with me. I wait for it. “If you don’t mind me asking,” one starts, and I suppress a sigh. “How do you speak such good English?” Because India was colonized by England for a few hundred years, I wanted to retort. Because not every Indian has the accent and vocabulary of a stereotypical scam caller like you think. “I grew up in a pretty urban area, so English was really common,” I say instead, with a plastered smile. It isn’t ever racism I battle, it’s just mostly willful ignorance. It always enforced the idea that there was them, and there was me. And no matter how hard I tried to bridge the gap, it would always remain. As interactions go, this wasn’t the worst. There was that one guy who had asked me if we rode elephants to school, and the visual of an elephant lumbering down Marine Drive, one of the busiest roads in the city which wound around the sea, during rush hour had nearly made me laugh from absurdity. There was no place that an elephant would have been more unfit for, sometimes reminding me of my own situation. I was the elephant on Marine Drive in Math Lab that day.

Maybe it was my fault for not engaging with the international community when I first got here, but as a member of the Michigan Research and Discovery Scholars, my first few weeks were a blur of orientations and research lab applications and interviews mixed with a healthy dose of trips to frat row and Joe’s Pizza. I made a closely-knit and diverse group of friends in MRADS, but I still felt out of place at times. My non-Indian friends have now seen Bollywood movies, celebrated Holi on campus, eaten authentic Indian food and learned a good number of Hindi insults. They are understanding, curious and accepting, and I love sharing my culture with them. But I also get a high frequency of questions from strangers and acquaintances, and sometimes, it grows tiring contextualizing my existence — explaining the idol of a Hindu god in my room, answering why Indian weddings last a week, retorting to questions about whether I’ll be forced into an arranged marriage. When I talk to my friends from home, I’m so relieved that they just get it. Like me, they call it a “petrol pump” instead of a “gas station” and “Bombay” instead of “Mumbai”. We have shared memories of the city that I love: speedboat rides departing from the Gateway of India in the glittering Arabian sea and playing basketball on the sun-dappled orange-and-green outdoor court at school. We laugh and I reminisce on old times which feel a lifetime away: being penalized for an untidy school uniform on Monday assembly mornings, frantically getting maps of India printed at a craft store for geography class the next day, the gray and blue afternoons during monsoon when big puddles on the road would reflect city lights and the next second be disrupted by the giant wheels of colorful trucks with musical honks. My friends and I had a shared memory line for 18 years that had diverged; suddenly I had lived new experiences without them. Late night ping pong matches in the Jo living room, Saturday mornings visiting the farmer’s market, the mad rush back to the dorm with my friends in the snow (in clothes completely inappropriate for snow). As much as my experiences in Mumbai had shaped my character, my experiences in Ann Arbor slowly did too.

As I end my freshman year, I like to think that I’ve assimilated to life here. I’m now used to sometimes being the only non American person in the room, or even being one of the few people of Color there. I can do a rough conversion from miles to kilometers in my head while running on the treadmill and understand that when someone says “it’s 40 degrees outside” they mean around zero degrees Celsius. When I ask someone where they’re from, I’m no longer baffled when they point a finger to a random spot on their palm. After an incident at Starbucks in East Lansing (I now know why we hate that place) I say wa-ter instead of wo-tah, and, much to the chagrin of my friends at home, my accent and pronunciations are changing for ease of understanding. I’ve grown to love Ann Arbor — the vibrancy, the accessibility, the charm. Although it’s been a learning curve to fit in completely, each day I feel more and more like a part of the community. I am no longer an elephant on Marine Drive who feels out of place and stared at by onlookers. Some days I’ll still look around in amazement at how quiet and calm life feels here, as compared to the riot of color and chaos of Bombay. When I return home this summer, it will be a different version of the girl who left last August. I’m more confident in myself and my abilities now — I was able to move to a new continent as a teenager alone, build a community for myself and adapt to my new life. I also go home with a sense of appreciation for Bombay that I never had. I didn’t know how important my city was to my identity until I left, and I will never take for granted the ease I feel there again. There’s a certain power and relief in being in your natural habitat, a place where you don’t have to try to fit in and you can just be. Even as I grow more and more at home in Ann Arbor, when I jump into an Uber or make a quick CVS run, I feel the ghost of a word on my tongue — a niggling sadness that I can never go outside and call a stranger bhaiya.

Statement Columnist Myrra Arya can be reached at myrra@umich.edu